Influencing stakeholders as part of workforce planning

Stakeholder Mapping

Thinker on management and information systems, Aubrey Mendelow, created a two-by-two matrix of power and dynamism as a method to support environmental scanning. Power is an important axis in the model; whilst we tend to recognize stakeholders with power it is important to understand the sources of power in order to be able to compare it against other stakeholders. Power gives stakeholders the ability to restructure situations2 and can arise in four key ways: possession of resources, ability to dictate alternatives, authority and influence.

- Possession of resources provides a significant power base, hence the enduring power of unions in certain industries.

- Aligned to this possession is the ability to dictate alternatives: the availability of alternative resources reduces the power of the possessor, equally the sole supplier has the greatest of power.

- Authority, the right to enforce obedience, has always remained an important source of power. This could be in the form of government and regulatory bodies, but it is equally found in the bureaucracy of organizations in their ability to hire, pay and dismiss workers.

- The final source of power is influence, the ability to sway those who hold power in other ways. By considering stakeholders on the basis of power, we see them in line with Freeman’s stakeholder theory that stakeholders are more than simply the business owners.

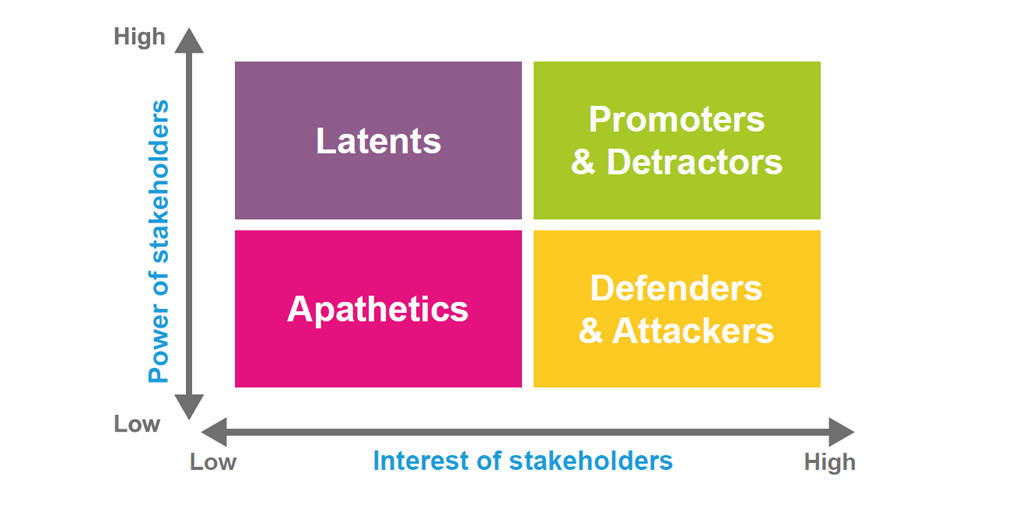

Rather than the second axis of dynamism, Mendelow’s matrix is adapted to include interest, to create four specific groups: apathetics, latents, defenders with attackers, and promoters with detractors.

- Apathetics have both low power and low interest, those who can be engaged usually through general communications.

- Latents have low interest but high power, therefore it is essential their needs are met. With this group it is important to engage and consult on areas they are specifically interested and aim to increase their positive interest. Equally, with activities likely to easily stir angst, it may be more prudent to downplay initiative to reduce the risk of creating attackers.

- Attackers have low power but high and negative interest, they fall into the same quadrant as defenders who share low power but have a high positive interest. Defenders are potential supporters and ambassadors. If engaged in the right way, they can be a useful area with which to both consult and potentially involve in low-risk areas. Attackers can reduce the ability of defenders and attract apathetics to their cause, therefore defender become valuable as ambassadors to neutralize negative opinions.

- Promoters and detractors are our key stakeholders and where we need to focus our efforts. Both have high interest and power; promoters are supportive and dectractors are negative. Not only must they be engaged and consulted regularly, but they need to be involved (if not already) into the governance and decision-making. The aim is to keep promoters onside and to either convert detractors into positivity, or otherwise neutralize them either through the use of promoters or through creating a groundswell by converting latents.

Engaging with stakeholders

The key challenge to overcome at this stage is to convince a stakeholder to let us provide a firm evidence-base from which decisions around the workforce can be made. The tendency is for stakeholders to favour particular initiatives or courses of action before the evidence is presented or the problem understood fully, a tendency that will be based heavily on cognitive biases. The four main biases we are aiming to overcome are: anchoring; attribute substitution; the availability heuristic, and; pro-innovation bias.

- Anchoring is a concept where people depend too heavily on an initial piece of information when making a decision.4 If we arrange a meeting with a stakeholder to discuss workforce planning and one of the first things we mention is diversity, then the meeting may well anchor to that specific factor.

- Attribute substitution is where the complexity of the situation is substituted for a heuristic, either the anchor or some other factor, and then judgement is made based on that substitute.5 For example, a stakeholder may focus on a specific factor of workforce diversity, like gender balance in the executive board, as a heuristic for the wider challenge of improving the diversity of the workforce.

- The availability heuristic is a mental shortcut where examples that a stakeholder can recall are viewed more strongly than alternatives.6 Stakeholders will either recall initiatives that others have implemented, or ones that they themselves have implemented, and promote those.

- The pro-innovation bias is where a stakeholder has such a strong bias in favour of an initiative that they are unable to see the weaknesses or the limitations when applying it in a new situation.7

These biases, either separate or together, will often result in what I call stealing other people’s artificial grass. Stakeholders have either seen that another organization has taken a particular action, or they themselves have done it in a different organization. Some are unaware of the specific relationship between the action and the effect that is created; others are thinking that the problem the action solves is the same as the challenge we are presenting. Depending on our relationship with stakeholders, we can either challenge the bias or pivot.

Agree terms of reference

The critical final stage is to agree the terms of reference for the next stage of workforce planning. If we are well established workforce planning function, we may have a green light from key stakeholders to continue through to action plan and possibly to deliver within certain tolerances. If this is a new function, then this stage may simply focus on gaining agreement to proceed to the next stages of supply, demand and gap analysis. Regardless of the aim, it is critical that we have clear agreement from key stakeholders on the following areas.

Organizational Levels

Firstly, we need to agree the level of the organization on which we will be conducting workforce planning. The power of our stakeholder is a key determining factor: we will be unable to operate effectively at the macro level if the power of our stakeholder is limited to the meso level. If we are operating at the meso level, be specific around functions and departments.

Roles of Interest

In agreeing the organizational levels, we will also need agreement on the roles of interest in this exercise. Be clear around the rationale for those roles: the cohort needs to be of sufficient size that an exercise in workforce planning would be able to achieve a return on the investment of time.

Workforce Analytics

Having agreed the roles of interest, we also need to agree the workforce analytics. Crucially, this must include the counting rules: the characteristics that determine those who are in or out of scope. These counting rules may relate to the exclusion of contractors or the inclusion of those on secondment. Agree the broad approaches to how we will model and forecast both supply and demand, which we will cover in the next two parts of the book. The importance of this is to avoid surprizes at a later point in time, we do not want to be discussing the forecast further down the line and a key stakeholder have a fundamental disagreement with our model.

Horizons

Next, we will need to agree the planning horizon. If this is a new venture, then planning at a minimum of horizon two (the next budgetary year) must be the minimum time period. In my experience, planning in an organization with a low maturity in workforce planning, can be slow. Therefore, planning in horizon one may take longer to get to execution than the timeframe of the forecast. As organizational maturity grows, our speed to conduct a workforce planning cycle will increase and allow us to deal with a shorter timeframe. If we are looking at planning in horizon three for the first time, then it is wise counsel to set the limit where are we are able to forecast with an accuracy of plus or minus twenty percent.8

Scenarios

Finally, we will need to agree the scenarios. Scenarios are a qualitative explanation of how the present might evolve to the future and the plausible variations of that future.9 Therefore, the basis of these scenarios will be the strategic alignment, environmental scanning and understanding of the workforce that we have already conducted within the context of the planning horizon we have agreed. Firstly, what is the organization planning to do: does it plan to grow or maintain its revenue, and is it planning to improve in a different metric (brand advocacy or sustainability, for example)? A consideration at this stage is if the organization already has specific strategies or plans in place that relate directly to the workforce: is there already a commitment to close a workplace or to outsource work? Finally, we consider the future on the basis of the environmental scanning, what Porter calls ‘macroscenarios’10. Firstly, what do we anticipate might happen in the future regarding our business and what is the likelihood of those events? For example, how attractive do we expect our industry to be and are we vulnerable to disruptive technologies? Secondly, do we anticipate any significant changes that will impact our workforce and what is the likelihood of those events? For example, a political change that could impact the flow of migrant workers.